(日本語版はこちら)

Hello, this is Shingo Emoto. I appreciate you listening to me again. A little while ago, Setsuko Sato explained the word “Yohaku”, which symbolizes the Japanese aesthetic sense, through “Shohrin-zu” drawn by Tohaku Hasegawa. From now, I would like to talk about paintings of Jakuchu Ito and the Japanese view of nature that lies behind his paintings.

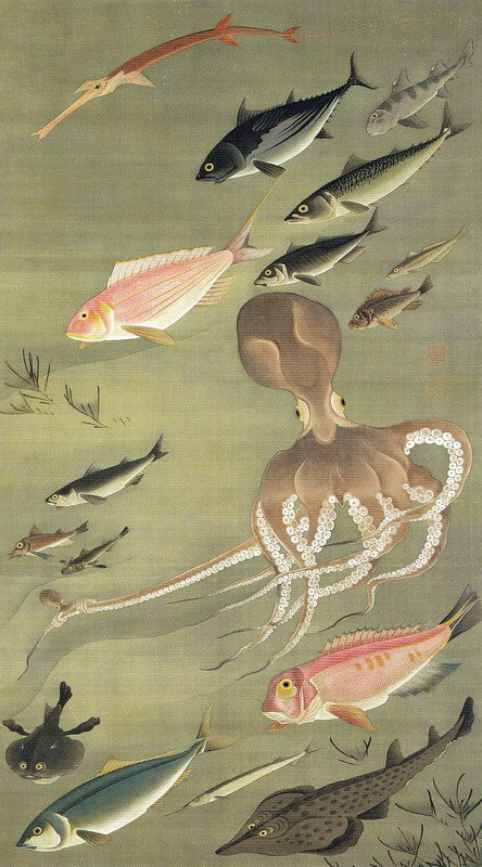

Jakuchu was a painter who was active in the Edo period. In recent years, he has come back into the spotlight and is now counted as one of the most important painter representing Japan. First of all, let’s take a look at some of his masterpieces without any explanation.

How were they? Many of you may be surprised by the difference between Jakuchu’s paintings and Tohaku’s “Shorin-zu” introduced by Sato-san. In “Shorin-zu”, the empty space, called “yohaku”, is the

main feature of the picture. In contrast, Jakuchu was painting the entire surface of the canvas. This massive energy covering the entire screen is one of the charms of Jakuchu.

Furthermore, the entire screen is not just filled, but personalities of each things on the canvas are painted in detail without missing a single thing. For example, if you look at this painting on the left, you’ll see that each dog’s pattern is uniquely drawn without being stereotyped.

Or, if you look the lotus leaf in the lower left corner of this painting, you can see that even the holes created by insects are carefully painted without omission. It is one of his characteristics that he draws everything very carefully so that he loves each and every one of them.

Another important characteristic of Jakuchu's paintings is that not only animals and plants, but also fish and insect are featured as motifs, and even as main motifs.

Actually, Jakuchu was an enthusiastic Buddhist as well as a painter. It is said that the Buddhist view of nature implied in the word 草木国土悉皆成仏(Sou-moku-koku-do-sitsu-kai-jou-butsu) has had a great influence on his paintings. Grasses, trees, and soils and stones that make up the land, all of them are able to become Buddha, which is the meaning of this word. That is, in Japan, not only human beings and animals, but also plants such as grasses and trees, and even soils and stones are thought to be able to attain enlightenment and become a Buddha. Even the most insignificant beings, which are usually unnoticed by people, are endowed with Buddha-nature. Everything is as precious as the Buddha and is equally valuable. Such kind of Japanese philosophy about equality is embedded in the eight characters of 草木国土悉皆成仏.

Based on this philosophy, Jakuchu painted his paintings without neglecting any tiny beings like small insects crawling around our feet, leaves with holes that had been eaten by those insects, patterns of the individual puppies and chickens, or the individual feathers of those chickens and its every strand, as he devoted himself to everything.

In addition, an animistic view of nature, which has been inherited since the Jomon period in Japan, lies at the bottom of the view of nature in 草木国土悉皆成仏. Animism is the idea that everything in this world is a living being with a spirit in it. We, Japanese, traditionally have thought that not only humans, animals, and plants, but also things like soils and stones have a spirit in them and are alive. Therefore, we can easily believe that they also have Buddha nature and are able to become Buddha.

In this animistic nature where everything is alive, from grasses and trees to soils and stones, Jakuchu captured their lives on his canvas. He was active just in the era when the concept of

写生(sha-sei) was first introduced from China. It means “sketching” in English, but literally “capturing life”. So, 写生 is not just copying the superficial form of a motif, but also capturing the

way it is alive.

I heard that many people in Romania came to love Japan through Japanese anime. I think this animism is probably related to the reason why Japanese anime is so popular around the world. Because,

the essence of animation is the art of putting on a screen spirits, souls, and lives existing in everything (“animism” and “animation” share the same root word “anima”), and this art is

considered to be developed well based on the ancient Japanese view of nature such as animism or 草木国土悉皆成仏 as well as Jakuchu’s art of 写生 was.

In the presentation I did a while ago, I said that I wanted to establish a new methodology of science rooted in the Japanese view of nature. In the case of animation, we have done well. I believe that we can do it in science as well. A science that does not materialize things, but touches their lives. For example, I am trying to explore the possibilities in the philosophy of 民芸(min-gei), which will be introduce by Hashiguchi-san. That is what I am working on at Shoyosha now. Thank you for your listening.

Shingo Emoto/江本伸悟

コメントをお書きください